| Inverary, Old and New |

Inverary

Inveraray is a township in the west of Scotland on the shore of Loch Fyne, north of Glasgow. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century it was the seat of the Earl of Argyll and the main centre of the Campbell clan. The old town which our ancestors knew was not on the present site but at the mouth of the river Aray between the castle and the Loch.

The flat land was leased to crofters and the valley of Glen Shira just north east of the town and was the bread basket of Inveraray which had a large number of residents then. Each week country people carried wool, cheese, feathers, eggs, broom, salmon, and skins to the market and the occupations of fishing, hunting, agriculture, cattle and sheep rearing, curing of hides and iron working received encouragement.

The following two extracts from "The Royal Burgh of Inveraray" give some indication of what life was like.

|

Page 102 states that

"The produce of the country which was sold at market was great oats, small oats, groats (the grain of oats deprived of their husks), salt beef, butter, wool, candles and tallow. The wealth of the people consisted in their cattle: Kyloes (small highland cattle having shaggy hair and long curving horns), horses, sheep, goats, and pigs and in these was brisk trade. Drovers were present, with sums of nine or ten pounds sterling, mostly consisting of forty shilling pieces, carried in a belt around their middle.

The people subsisted, as might be deduced from the articles for sale at the market, on meal and fish, on goats milk, cows milk and mutton. Brewing took place in houses in the Autumn, and at that time some people were always fou, being both in drink and somewhat distracted.

The clothing worn by men was a cloth coat, sometimes spoken of as a cassog, a pair of breeches, a pair of trews, a pair of hose, a bonnet, a belted plaid, and a pair of shoes. The garments most often mentioned as being worn by women were plaids and red shag petticoats; that is petticoats made of cloth with a rough nap. Both men and women were given to idle vageing or going for walks on the Sabbath day.

The lives of the poor make sad reading. Some gathered shellfish in the month of September. One woman sought shelter in a wast or deserted house where no person lived, without light of fire, candle or food for her entertainment. Another poor and indigent woman came to a field where people were sowing corn, to seek alms and charity and obtain some small quantity from some of the people sowing, which she would keep in a little poke or apron about her, this being the only means to preserve life.

|

|

|

|

|

In this modern photo, taken from the lookout tower, the new town is on the peninsula and the castle

is hidden at the foot of the hill. The old village was between the castle and the Loch.

When Ian saw it in 1952 the hills were all treeless apart from areas near Inveraray.

The big timber trees would have been gone by the mid 1600's, but when iron smelting was started in 1775,

it was to use "the plentiful supply of scrub timber" for charcoal so the hills were not bare then.

The buildings of the town ranged from solid houses of squared stone with slate roofs for the better

off, to those of rough stone or of turves (failes) with thatched roofs.

|

|

|

|

Extract from "Scotland's Story" by Tom Steel, published 1984, pg 216.

Chiefs became caught up in the new Lowland concept of commercial landlordism. Most of the Highland nobility were educated men, who shared the more polite culture of Lowland Scotland, and many began to better their estates on the Lowland model.

Although Argyll managed them from London through regional chamberlains or baillies, he was a conscientious, well meaning landlord.

In three years, between 1779 and 1782, the population of Argyll rose by a fifth and the Duke attempted to stimulate industry and fishing to provide a living for his people.

Kelp manufacture, the burning of seaweed to provide alkali, boomed during the long wars with France, and gave tenants work. In the 1760's kelp prices were about £2 a ton.

Within 30 years, the price per ton had risen to £10 and by the early 1800's the landlords of the Hebrides alone made profits of £70,000 on an annual export of twenty thousand tons of kelp.

At Inverary in 1743, the Duke of Argyll began to build a new Georgian village. Inveraray, the Duke hoped, would become a base for herring fishing in Loch Fyne; but the cost of building the town was immense, and he, like many lairds, relied overmuch on the boom in kelp prices to finance it's construction.

But when peace came in 1815, the kelp industry waned and only a high import tax on foreign alkali made from narilla kept the Scottish industry alive until 1823.

|

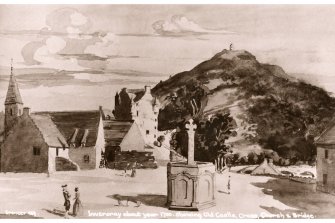

Reproduction of an old painting circa 1700 , showing the original castle and the mercat cross in the marketplace.

On the right is the original double arched bridge, and on the left is the church in which the trial of James Stewart took place in 1752.

|

|

The same mercat cross (built originally in 1330-1400) in its new home in the rebuilt town, overlooking Loch Fyne.

|

|

Page 106 goes on:

"As the seventeenth century wore on, the town of Inveraray became more and more throng. There was a sheriff in the person of Mr Alexander Duncanson in 1681; there was a notar Mr Duncan Ffisher and a writer; there was a poet, Duncan MacIntyre in Braleckan (circa 1652-1683) who wrote an elegy Cumha Teaghlaich a Mhain,

mourning for a family called McKellar who held the farms of Maam and Kilblaan in Glen Shira. There was an officer home from the wars (of whom there have always been two or three in Inveraray in every generation), in this case he was Major John Campbell of Clonary; there was a poor soldier lately come out of Barbados. There was the schoolmaster, the usher, several poor scholars and the landladies who kept the scholars.

There was the miller and the miller's knave. There were merchants expecting the arrival of lowland boats with merchand ware. There were shopkeepers, change-keepers, brewers and malt men. There were tradesmen a-plenty: slaters, locksmiths, glovers, weavers, tailors, coriners, or shoe-makers, joiners, saddlers, and wrights. There were gaein'-abootbodies: hawkers, tinclars, sorners, vagabonds, and wandering pipers who would play for a dram in any house.

Of more substance were the coupers, dealers in cattle and horses and the drovers. There were some who magnified their office: the beddal, bedral or beadle, the messenger, the public crier who affixed his proclamation to the most patents yeatts of the house. There were those who worked on the estate, the gardener and the forester. There were those who went down to the sea in ships, skippers, ferriers, and fishermen: and those who awaited their return, the fish curers, the gutters, and the packers.

There were the poor: a leper, an old man with a lunatick oy or grandson, relicts of former citizens who supplicated the Kirk Session for some supplies.'

The town guard carried out the services of watching and warding within the burgh. The watch was made up of citizens, two of which (or their proper substitutes employed by them) were to be on guard from ten at night until six o'clock the next morning. Their headquarters were the tollbooth and they were armed with halberds.

The language throughout the area was originally Gaelic, but as the official language of the burgh was Scots (or English). Many of the townspeople were bilingual by the mid 1600's. In the late 1700's only the country folk used Gaelic, but it was not until the latter part of the nineteenth century that the use of Gaelic declined seriously in the rural areas. Even in 1951, there were still under 10% of the parish who spoke Gaelic

|

|

The first mention of the Inveraray and Glenaray parish was under it's original name of Kilmalduff parish, later written

as Kilmolew or Kilmalieu, when its rector was witness to a land grant in 1304. At that time the village consisted of a

few fishermen's huts of wattle and daub or turf at the mouth of the river Aray with patches of cultivated ground.

Close by was the church and the mill on the river, although much of the oats were ground by hand querns, especially in

winter when the river was frozen.

Major steps forward occurred in 1432 when the castle was built by Sir Colin Campbell, first Laird of Glen Urchy and

after 1457 when it became the main residence of the Earls of Argyll. In 1474 it was created a Burgh of Barony,

entitled to hold weekly markets and 2 yearly week long fairs. It had special trading and herring fishing rights and

was allowed Burgesses and Bailies and any other officers needed. The Burgesses were farmers who held their property

of the Earl of Argyll - they were his vassals. Bailies, Aldermen, and Provosts were appointed by the Earl.

A burghal court was constituted at least twice yearly. This was presided over by the Baron (The Earl of Argyll) or by

his Baron Baille when the Earl was in Edinburgh or abroad. All the Burgesses attended on the Baron court; infringements

of the law were dealt with and the statutes were promulgated concerning the conduct and administration of the Burgh.

The fortunes of the Earls of Argyll, the clan Campbell, and Inveraray continued to rise until about the time our first

known ancestor John The Knock was entering this world of woe. At this time, a royalist army under Montrose drove back

the Argyll covenanters, sacked the town and district, then followed them up to Inverlochy where the covenanters were

cut to ribbons. This may have been a simple matter anywhere but in Scotland. The McDonalds had been lords of the Isles

for generations, holding a kingdom from Northern Ireland up the west coast and the islands of Scotland. As their power

waned, the Campbells' grew and by the 1600's the McDonalds were considerably reduced.

As the Earl of Argyll was a leader of the covenanters, the McDonalds came out for the King, led Montrose into Argyll

and were foremost in the sack of the parish and the slaughter at Inverlochy.

Inveraray took many years to recover from the destruction of that time and the Glencoe McDonalds under the McIan,

their chief, continued to make cattle raids into the Campbell country and beyond, sometimes on their own, sometimes

with allied clans, and sometimes into the lowlands. They were regarded by many as brigands and in 1692 the King

finally ordered them to be eliminated. The massacre at Glencoe would have gone almost unnoticed had the soldiers

not been sent in and quartered on the McDonalds before final orders were sent to kill the people who's hospitality

they had received. Perhaps the poor co-ordination of the action which saw many escape was a protest against this

breach of honour.

Prior to Glencoe however, Argyll received the heaviest blow of all. The King took offence at a protest of the Earl

and ordered his death. The Earl fled, then returned in 1685 with an attempted uprising. The Marquis of Athol had been

placed over Argyll and with the aborted uprising, he set about a systematic destruction and depopulation of the area.

A good year for the herring gave the people a chance to survive but the boats were broken and their nets burned.

Again, it was a long time before the parish recovered.

Recovery did take place and during the early eighteenth century Inveraray prospered, comparatively speaking.

It was in 1734 that John McNuier III became post runner and between 27th April and 31st December of that year more

than 2,450 letters were handled by the Inveraray postmaster and in 1744 a military road was built between Inveraray

and Dunbarton. Up to this time wheeled vehicles could only move in the immediate vicinity of the town and much of

the travel was by sea.

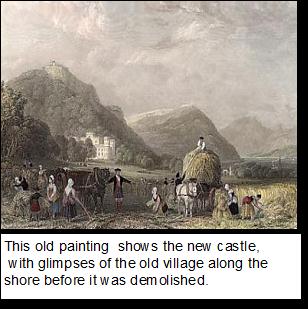

The Duke was building a new castle and needed space for the castle grounds, so in 1743 he commenced building a new

Georgian village in its present site on the peninsula. In 1746, he issued an order of removal to many of the

inhabitants. In 1771 - 1773 the old castle and buildings of the old town were demolished and the building of the

new town continued. When the new town was being constructed, some of the locals were reluctant to move from the

old town. Newspapers printed in 1753 include a "Precept of Warning" against persons described as

"pretended Tennents and possesors of Tenements in Inverary", which included the name Alexander McNuier, Fisher.

We cannot be sure if this was our ancestor Alexander prior to his marriage to Catherine Ferguson -

they lived in Glen Shira just north of the town, so it may not be them. There were many McNuiers in Inverary

around this time. In 1758 the Inveraray Paper published a list of inhabitants who still had not moved out of

their homes, and were given until Whitsunday to move - listed here is "Jannet McIlchattan, relict (widow)

of Wm McNuyer, workman" - not sure who this is.

The starting of a kelp industry in 1760 which burned seaweed to produce potash, boosted the economy for many

years and in 1775 the smelting of iron was started using the "plentiful supply of scrub timber" for charcoal.

So gradually civilisation was coming into the lives of the Inveraray people but theirs was a hand to mouth

existence at best and their possessions were few.

|

|

|

|

|